Coastwatcher deaths slipped from history. Even in New Zealand, where it could have been a major tragedy, it was lost in secrecy and the wider war that had killed thousands. The savagery of the Japanese was truly astounding even before world war was underway. The December 1937 capture of Nanking saw the Japanese rape, torture and murder more than 300,000 Chinese civilians, more than the combined number killed in the atom bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki eight years later. There was the Bataan Death March and the Burma railroad. There was an incident in October 1943 when US ships bombarded Wake Island. The Japanese rounded up all 96 prisoners and machine-gunned them to death. The Japanese bayoneted 90 prisoners to death on Balalai Island in the Solomons after hearing the Allies were heading toward them.Coastwatchers from the northern end of the Gilberts down to the Sub-Antarctic Islands never saw a German and by the time they were in place most of the Nazi raiders had gone. This is not to say the idea of coast watching was folly. Knowledge that eyes were watching scattered parts of the Pacific would have given planners and sailors some reassurance, although it might well have been misplaced. It was clear almost as the men were being placed on the Gilberts, that the real concern was not Germany, but Japan. The concept was wrong. Watching for a solitary hostile ship is one thing and certainly not particularly dangerous; standing helplessly before a huge military machine is fatal and pointless. New Zealand did not have men to waste like they did in the Gilberts. The coastwatching system worked exceptionally well in the Solomons and the presence of men scattered all the way through that archipelago made the difference between victory and defeat on Guadalcanal. Some of the coastwatchers looked down on distant Japanese bases. When in danger they could be rescued. There are stories of submarines prowling into the Bougainville coast to take off coast watchers and nuns. A US submarine, S-38, was off Tarawa as the coastwatchers were being seized. Heenan, Owen and Speedy were just 15 kilometres from it a day before they were captured. The crucial difference between the Solomons and the Gilberts is in the hinterland. In the 1980s a nasty guerrilla war was fought in Bougainville precisely because the country had a rugged, inhospitable and often inaccessible mountain heart. The key islands in the Solomons were the same. You could be a coastwatcher and you could hide. What were you to do on an island that was never more than five metres high, where you could stand in the middle and throw a rock left or right and hit water. Even in a place like Tarawa, where hiding was possible for a time, the Japanese showed no restraint in threatening the indigenous population; hand over white men or else.

Stan Brown blamed the WPHC for what happened.

‘The High Commission arranged for the escape of its employees, the three district officers, but nobody took responsibility for the coast watchers,’ he said. ’Even after the Japanese had taken the three northern atolls, they did nothing about the men who were civilians. They could have legally been shot as spies for what they were doing.’

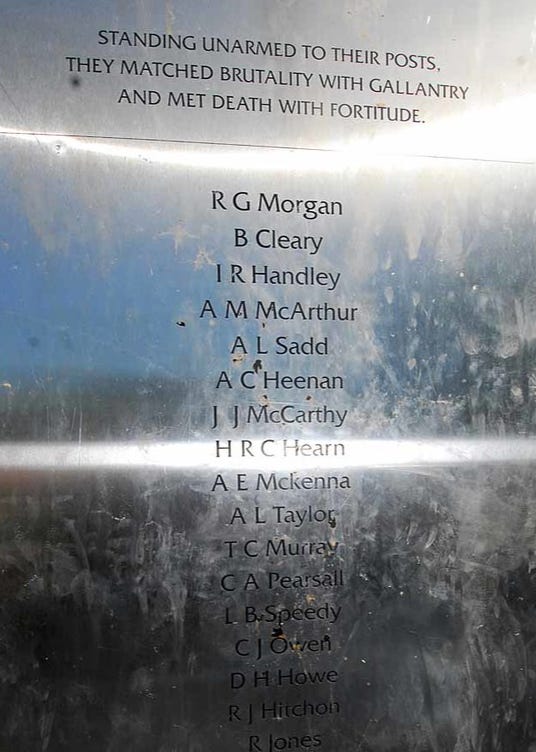

Twenty-four days after the executions, New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser sent a message to the coastwatchers, oblivious to their fate, praising them for the ‘magnificent manner’ in which they carried out their duty. ‘The example set by the coast watch organisation is an inspiration to us all and will never be forgotten.’

It was and quickly. The country that sent them into what they believed to be a backwater betrayed them and the danger was much more severe than they let onto the men. Even when it became clear the coastwatchers were in severe danger nothing was done to get them out. Their role as tripwires was regarded as worth their freedom, ultimately their lives. They could have been rescued; after all, if submarines could have taken in Carlson's Raiders, they could have taken out 17 coastwatchers. Flying boats could have got them. Perhaps, in the fog and friction of war, the men were not so much forgotten, but rather overlooked.

John Jones is among those who believe there was plenty of time to get his fellow radio operators and soldiers out. It was ill conceived, ‘the ultimate blatant waste of so many young lives by the New Zealand Government’. The men themselves, he believed, knew they were expendable. The Japanese, he said, were hoping that New Zealand would pull out the coastwatchers after the three northern atolls had been captured. This belief would explain why, he reckons, there was 10 months between the capture of the Southern Gilberts coast watchers and those in the north.

Tom Shaw, a radio operator in Fiji, agreed.

‘When the first three islands were taken the writing was on the wall, they should have sent a ship in and got them out.’

Brown was one who lived a long life after the war but did not forget those he had taken to their deaths. He acknowledged that in war mistakes were made. But while the coast watcher idea was timely it had been a mistake to send civilians.

When the first islands were taken it was obvious that the enemy could occupy the group when they wished and that no force was available to resist them. The available forces were fighting hard to keep a foothold in the Solomons and New Guinea. The authorities must have known this but no move was made to give the men permission to escape with the Tarawa escapees or by the Degei,

Given permission to leave, the coastwatchers at that time had many friends among the islanders who could have moved them from island to island. The essence of all leadership training is that the welfare of the troops is the most important consideration. Yet three district officers were allowed to escape while no such opportunity was given to the coast watchers. If the Allies were relying on their reports to invade the islands, there would have been justification for sacrificing them, but there was no such intention

Doug Hearn believed the death of his brother Rex was covered up to hide an ill-planned operation. Bitterness relatives feel is directed toward the Japanese but there is much hostility towards the New Zealand government. To their way of thinking, the men were the ultimate in expandability. The official war history, put together after the war to rationalise and explain, said the coast watching stations supplied vital information to the Allied commanders who had no other means of securing it. There were insufficient aircraft for the job and the Gilbert Islands, in particular, provided descriptions of Japanese aircraft, ships and submarines that were vital to the war effort. Significantly too the stations were deemed to have a passive value in that as they were occupied the Allies would know the extent of Japanese movement and occupation.

If the Japanese had been civilised in their treatment of prisoners this would not have been an issue. Like the seven men taken from the northern Gilberts who spent nearly four years in captivity, being captured was among the fortunes of war - except the radio men were not soldiers, not at least while they were alive. But the fate of the rest was the face of evil itself Could a New Zealand commander have reasonably expected his men would have faced this? Nanking was well known in New Zealand but there would have been a sense that the victims were Chinese, they were different; we were New Zealanders and the Japanese would have respected us for that. When the coastwatchers were sent out the extent to which this was to be a race war was not appreciated.

Finally, one has to accept that the Allies needed the radio operators and their eyes in the Gilbert Islands. It could be argued that the New Zealand approach to the Gilberts was a mistake. The islands, or at least Tarawa and Butaritari, should have been garrisoned. The size is a matter of debate but it need not have been large to be a reasonably effective deterrent. A small Allied force put on Tarawa might well have prevented the later bloodshed of the American occupation. Of course that is speculation; the Japanese did take Wake Island and did try to take Midway so perhaps a force on Tarawa may have simply attracted them to a greater force earlier. At higher strategic levels the nagging fear was of the Japanese but this was not so easy to admit publicly. For one thing most of New Zealand's forces were committed to Europe and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill showed no willingness to let Wellington bring them home. Canberra was much more successful at bringing its soldiers back, but it was done at fierce political and diplomatic cost. What happened in the Gilberts was part of the cost New Zealand paid for its ignorance of Pacific realities, and its lack of vision of planning.

They were people who suffered almost no public recognition, either then or since. Today it is hard to conceive of it, but in those days ordinary people on the streets thought of New Zealand's war as being in North Africa. Len Eldership served in New Caledonia as a signalman in the army. He recalled being back in New Zealand and based at Trentham when he and some friends went into Wellington. The Pacific men did not have the distinctive ‘New Zealand’ soldier flashes that the men from the European theatre had.

‘You could see the people looking at us, looking down at us,’ he recalled, ‘they thought we were nothing.’

They went up to the Buckle Street army headquarters and asked for shoulder flashes for the Pacific men. In the end they got them, but only after New Zealand soldiers had landed on Vella Lavella in the Solomons.

‘Those flashes were paid for in blood,’ he said.

Japanese intentions were not known and the extent of their military build-up in the Marshall Islands was a mystery, even to the Americans. Today Kiribati and Tuvalu are remote and poor island nations, of no great clout, although in the 1970s Washington worried at the prospect of the Soviets building bases there. Even today both countries are still required to consult with Washington should another power be interested in opening something as simple as a fishing base. Immediately after Pearl Harbour the shape of the map must have been terrifying to Allied military planners. The Gilbert and Ellice Islands looked like simple stepping-stones to Fiji in the first instance. When the Japanese interrogated the coast watchers from the northern Gilberts they asked about Fiji defences. Without the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway in May and June 1942 Fiji would have probably been in Japanese hands later that year.

Perhaps it was vital to have eyes and ears up in the atolls, although the addition of a couple of unarmed soldiers was a simple waste of two lives. Could they have been local people? Jones, who built up a life-long affection based on his five months with them, believes the Gilbertese were more than capable of handling the duties - they do so today. Reg Morgan on Tarawa was already training some local people, and on other islands locals helped out. We can only wonder if the Japanese knew. Colonialism was behind that not happening, and shows itself in the correspondence over Fiji. New Zealanders in Fiji were at first puzzled by the relationships between Fijians and Indians and the overwhelming presence of the ‘ruling 400’ as the leading whites were termed. Although close to New Zealand the atmosphere was tense and awkward. The coastwatching stations around the Fijian islands were given to Indian operators and Fijian coastwatchers. Official reports complained neither had ‘a first class knowledge of English’ and when an instruction was issued for them not to bother reporting the movements of friendly shipping they seemed unable to discriminate on what to report and they became useless. New Zealand soldiers were sent up in August 1942 to supervise but the Naval Liaison Officer reported they were ‘too old and unable to adapt themselves to the lonely conditions in these islands. There has always been much grumbling and, since Fijian lookouts are hired by the Government of Fiji to do the actual watching, the soldiers have little else to do than sit and think about their troubles’.

Jack Francis, the 17-year-old operator whose father would not sign the papers so he could go on the mission, has his theory about the killings.

‘My personal opinion of this event is that the Government was grossly at fault in not putting the telegraphists into uniform, as they were treated by the Japanese as spies and subsequently beheaded,’ he wrote. Perhaps he was right, except the Japanese killed a pastor and an old man that day.

Wartime is when risks are taken with lives. No commander can lead in combat without knowing, and accepting, that through his or her actions people will die, on his side. The responsibility is to minimise their losses. What happened in the Gilberts bares little sense as a strategy and contains all the elements of a committee forgetting the detail. They were under a hopelessly muddled command; the radio operators were from the Post Office, the soldiers were from the army, they were nominally working to naval intelligence and the British WPHC had some kind of responsibility. In that situation it is tempting to think that the others were taking care of the men on the ground. Certainly the idea that they were trip-wires is a beguiling theory but it makes no real sense here. The Allies knew, even without the coast watchers, where the range of the Japanese was and in the early days could do little to influence it anyway. As the war progressed and the men were left behind the quality intelligence was coming from intercepts and the growing power of the American submarine fleet. The information coming in from the radio operators was useful; but it was not priceless intelligence worth men's lives. And so, for the want of a decision, the men were left there. No one in Wellington or Suva expected that they were being left to die; but no one really knew why they were being left there.

Why slaughter 22 men in the fashion the Japanese did, including a blind old man? From a single incident it is wrong to extrapolate some kind of national or cultural characteristic, except the Japanese replayed Betio over and over, like some kind of total collective savage beyond all human restraint.

Jones saw the Japanese brutalising themselves. His Zentsuji POW camp was in the middle of what was a huge boot camp and he said he remembers seeing Japanese recruits being made to run until they vomited, and when they did, being beaten by other soldiers for doing so.

Commander Keisuke Matsuo, likely to have commanded the killing of the New Zealanders, was dead long before justice could reach him. New Zealand did not know that and as the Tokyo war crimes tribunals were being set up, the Crown Law Office looked at drawing up indictments against him for a war crime. It would have been the only one involving New Zealanders but because he was dead, the whole case was forgotten, both officially and historically.

When New Zealand was told finally what had happened to the coast watchers, the New Zealand Press Association reported that the Japanese commander responsible for the executions ‘got his’ in that bunker. They quoted Captain James Forbes of the Royal Navy Reserve who was serving with the US Navy; ‘The Japanese commander was killed on the second day of the action,’ he said. ’I saw his headquarters that day, a large concrete command post 30 feet by 15, with 34 inch walls. A 16-inch shell from a warship had gone right through it. I saw the body of the Japanese commander, and the upper part of his body was not pleasant to look at.’

Matsuo had committed suicide months before the landings.

©Michael J Field