Tropical madness worried Wilhelm Solf.

In German the malady was called troppenkoller—a term used to describe a peculiar set of symptoms supposedly endemic to the German temperament, especially among tourists.. The term described a set of symptoms supposedly specific to Germans, with some insisting it mainly affected tourists. By this definition, troppenkoller afflicted those who arrived in a tropical country believing their prior reading had made them experts—only to proceed to lecture the locals on how to live. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported in 1914: "In fact, Germans are not suited to the tropics; almost immediately they develop a complaint which they term troppenkoller - literally, tropical madness - to which the chief imports of German colonies, beer and champagne, add their mighty strength.’ Czech writer Franz Kafka referenced troppenkoller in his 1916 short story In der Strafkolonie (In the Penal Colony). Open to interpretation, the story could be set in a German tropical island colony - likely in the Pacific - though the ‘Officer’ is said to speak in French. One passage often cited in relation to troppenkoller occurs when the character known only as ‘Explorer’ remarks, ‘These uniforms are too heavy for the tropics, surely.’ The Officer replies, ‘Of course … but they mean home to us; we don’t want to forget about home.’ The cruelty attributed to colonial officials in the tropics - something Kafka was well aware of - was sometimes linked to troppenkoller. Solf, for his part, firmly believed in troppenkoller among German settlers. He estimated that 25 years was the longest Europeans could endure life in Samoa before succumbing to the malady. This was not a radical view at the time. In Deutsch-Samoa, one Dr. Bernard Funk even devised a solution: a cocktail called ‘Troppenkoller Remedy,’ still consumed in the South Pacific today. It was said to ‘restore self-respect and interest in one’s surroundings when even Tahitian rum failed.’ Originally, it was a mix of absinthe, grenadine, lime juice, and soda water. The artist Paul Gauguin was known to indulge in Dr. Funk’s concoction.

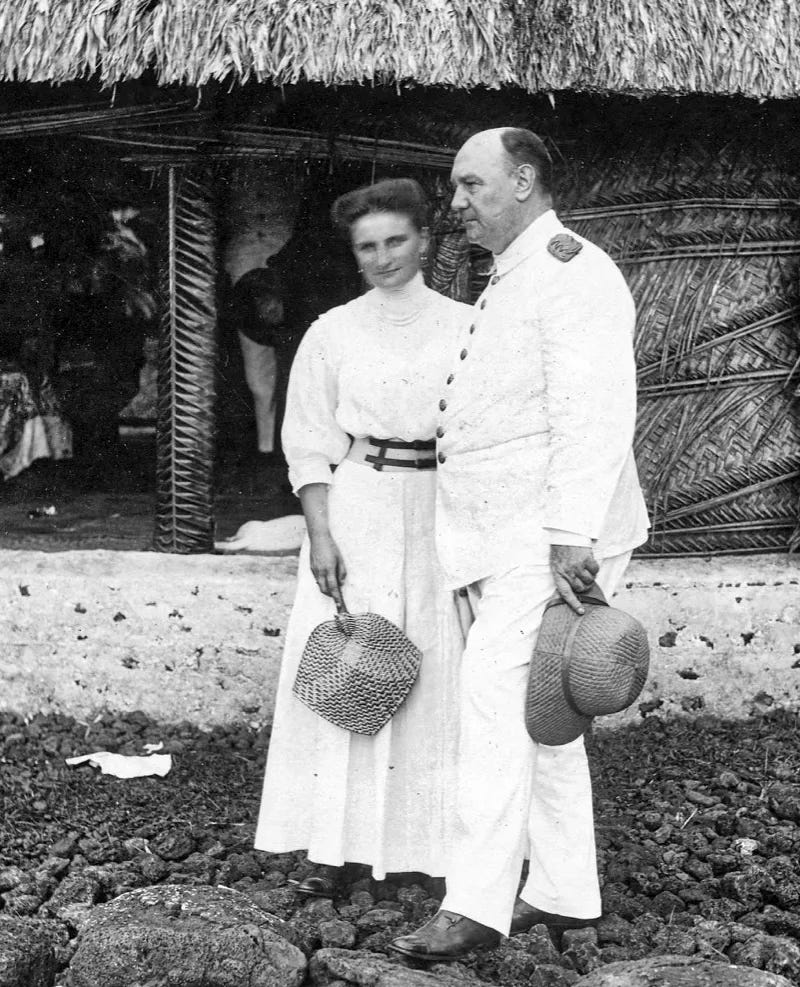

Solf’s irritability and prickliness were unlikely early symptoms of troppenkoller, but they did suggest loneliness. He governed a country filled with beautiful young women but was ideologically opposed to mixed-race relationships - presumably, he practiced what he preached. In 1908, he returned to Berlin on leave, where he courted (and was courted by) a woman 25 years his junior. The relationship had the appearance of an arranged match, yet their correspondence suggests genuine affection. They met at the spa town of Eisenach, northeast of Frankfurt. Johanna Elisabeth Susanne Dotti was born on November 14, 1887, in Neuenhagen, near Berlin. Her surname reflected her Italian heritage—her ancestor Giovanni Dotti had arrived in Prussia around 1800 to start a patent leather factory. By Johanna’s time, the family was thoroughly Prussian and financially secure. Her father, a successful landowner and local government official, also served as chief of police. He owned one of Germany’s first automobiles and enjoyed traveling the countryside with his daughters. Photographs of Johanna as an adult show a pensive, attractive woman, raising the question of how she ended up married to Wilhelm Solf. Not only was he much older, but he seemed a different kind of person - intense, career-focused, and devoted to duty and empire-building. Yet their marriage, solemnized in Germany, had genuine warmth. They returned together to Samoa, and in December 1908, Johanna accompanied Solf to Savai’i to handle a dispute with the tulafale or orator chief Lauaki, which ended in Lauaki’s deportation four months later. During their stay in Fagamalo, a photograph captures them looking like newlyweds on a honeymoon, seemingly oblivious to the official party around them. Savai’i, then an isolated and untouched Pacific island, was where Johanna likely conceived their first child. At Vailima, the Solfs lived in colonial luxury, with a full staff - including a Chinese nanny, or amah, for their expected child. On August 31, 1909, Dr. Funk climbed to Vailima once again, this time to assist in Johanna’s labour. Their daughter was born safely, though her name stood out: Maria-Elisabeth Augusta Margaretha So'oa'emalelagi Solf. The first three names reflected her Prussian heritage, but the fourth - Samoan for ‘a gift from heaven’—was telling. She was always known as Lagi, even by the Gestapo years later. The name raised eyebrows in the racially stratified Second Reich and even more so in the Third. Some questioned whether Lagi was adopted, given that she did not bear an obviously Aryan name. Yet the choice reflected Johanna’s worldview; she later named their other children based on their birthplaces. Their son, conceived in Samoa but born in Britain, was Hans-Heinrich Otto Georg Tupua Solf (Tupua being a Samoan chiefly name). Another son, Hermann, was given the Japanese name Isao.

After three years in Sāmoa, the family left for Germany, with Johanna pregnant once more. Solf’s longtime deputy, Erich Schultz-Ewerth, took over as governor, while Solf became head of the Colonial Office in Berlin.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Field's South Pacific Tides to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.