After the first wave of arrests, the Gestapo continued to investigate others they suspected of involvement.

One was Lagi’s friend and journalist Anton Knyphausen, Helsinki correspondent of Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, or DAZ. It was, inevitably pro-Nazi, while still managing to be one of the better Berlin daily newspapers. Knyphausen’s wife was Lagi’s childhood friend Armgard Michelet. It had been their wedding where there had been a solitary guest wearing a swastika armband. Wolfram Sievers had since risen high in SS ranks. When DAZ posted him to Helsinki, she could not get the necessary exit paperwork. She stayed in Berlin, caring for their young son. Knyphausen regularly visited Berlin to see his family. He would call on Lagi and attend Solf Circle meetings. In Helsinki he had a lover, Brita Gustafson, a journalist for the US United Press agency. He wanted a divorce. He was in Berlin in November 1943, a month after the ill-fated circle meeting, but before the arrests had begun. Laila Embelton, Armgard’s niece, relates what happened:

‘He was making, in his own words, “one last visit to Germany to see my elderly father and visit political friends”. It was on that visit that he received a phone call at his lodgings. The caller gave no name, but Anton recognized the voice at once; it was Sievers, his old friend from Wandervogel (a kind of scout organization that merged into Hitler Youth) days. He heard the voice clearly enunciating two words before hanging up: “Hau ab!” Get out of here! Another knew his friend was offering him a chance to save his life – while at the same time risking his own by making the call.’

Knyphausen knew enough to run and surprisingly, even without his baggage, he got to Helsinki. Finland, long fighting its old oppressor Russia, had ended up being on Nazi Germany’s side. As the war in the East went on, Finland became strategically vital for the Nazis. Hitler had paid one of his rare outside-of-Germany trips to Helsinki to underscore its importance to him. Berlin began diplomatic pressure to get Knyphausen sent back from Helsinki. He escaped to Sweden. Safe, he offered to work with the Allies. The journalist von Kardorff, who worked DAZ in Berlin, recorded in her diary that Knyphausen had gone to the other side: ‘He told me last winter he intended to. It is a bad thing for the newspaper, although he has not been on the staff for years.’ She said the ‘whole affair has raised quite a stink because it has been reported on the British radio’. Armgard was still in Berlin where conditions had steadily worsened. She was thin and ailing. She had known of the Helsinki woman and had to bear it alone with her son Edzard who had come down with tuberculosis. She was in need of help but her relatives, the Kuenzers, had their own worries. They lived in fear of the Gestapo as Richard Kuenzer had been in the Solf Circle. Embelton much later in life discovered a secret no one in the family knew: ‘It must have been some time in the spring or summer of 1942 that Wolfram Sievers approached Armgard, changing her life forever.’ He said Edzard could go to a sanatorium in the healthy air near the Swiss border. She accepted the offer. The price was to be an SS spy. Sievers introduced her to Otto-Ernst Schuddekopf, head of Amt V1, part of the SS intelligence service. They covered espionage in Western Europe. From 1943 she had been based in Stockholm, in the same city as her estranged husband. She operated across the Baltic and was in Finland often. She had high-level access, being a friend of the daughter of the military leader (and later president) of Finland, Carl Mannerheim. Back in Berlin toward the end of the war, Armgard worked as a translator for IG Farben, the company that made the lethal concentration camp gas Zyklon B.

There was one other astonishing side to the story. Before the war, the Michelet family was based in Brazil. The father was a Norwegian diplomat. Armgard was romantically involved with British diplomat, Paddy Noble. It came to nothing and when Armgard married Anton, Paddy Noble took up with her older sister, Sisi (Embelton’s mother). While he was based in Rome, he proposed by letter to Sisi, who agreed. She moved to Britain with him. When war came Paddy Noble was posted as the Foreign Office representative on the Joint Intelligence Staff working in Winston Churchill’s Cabinet War Rooms. Whatever vetting had taken place failed to pick up that the man with such a sensitive position was an in-law to a German journalist and his SS spy wife.

Home page photo: A 1943 edition of Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung

Available soon - Chapter 17 - Ravensbrück company

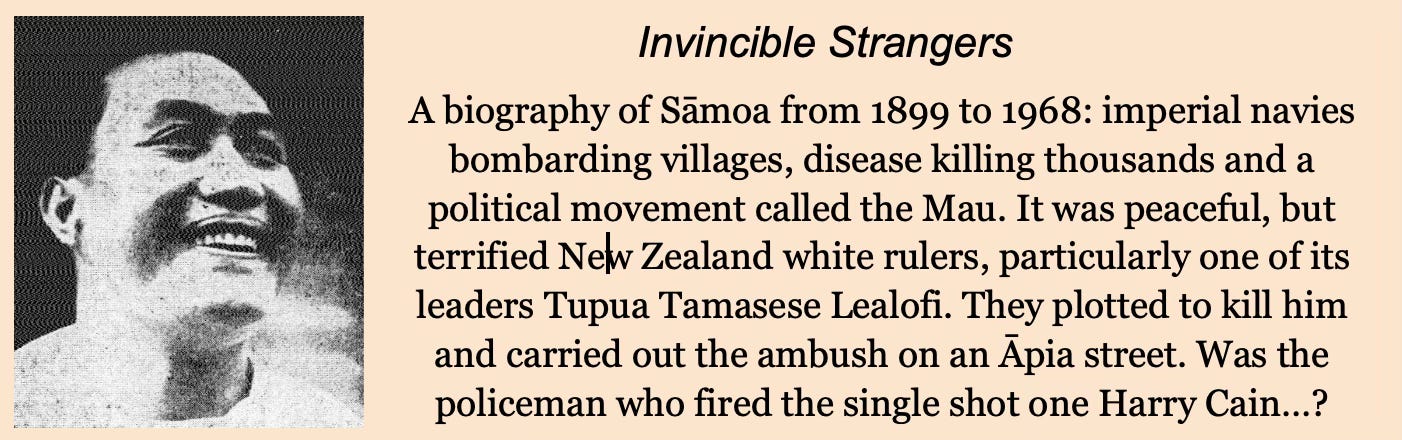

Contents: Dance of Death