Colonial New Zealand fantasised it would become headquarters of a southern empire, rewarded for its British values and success in transforming Māori from primitives to brown Englishmen.

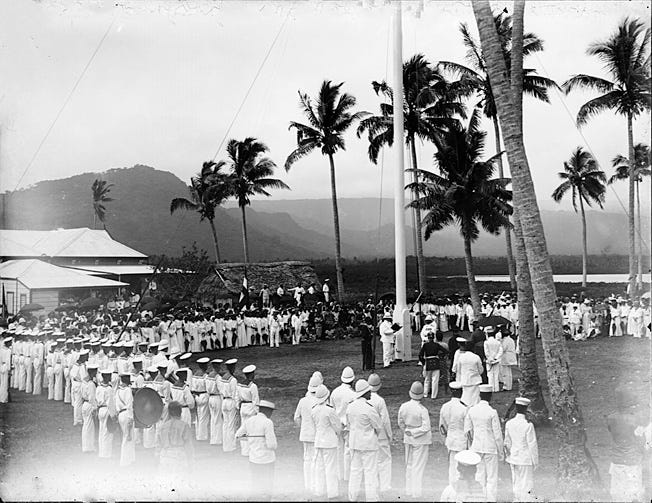

Hawai'i was part of the dream, Fiji too. Sāmoa, all of it, was the centrepiece of the New Zealand realm. That New Zealand had just 800,000 people at the turn of the 20th Century (Sāmoa 43,000) and was still dealing with the consequences of brutal land wars dispossessing Māori, was of no consequence. The process of memory blanking would become vital. Wellington had been particularly keen to get New Zealand soldiers into Sāmoa - they would have to settle for sending soldiers to South Africa instead, serving Britain in its dubious enterprise of seizing the Transvaal. New Zealand’s dream was formally put in abeyance on Thursday 1 March 1900. That day overdressed white people, many in assorted military gear with medals and swords, mustered at Mulinu’ū, still marked with shell craters. Solf called it ‘a small infertile spot.’ Men from SMS Cormoran formed up outside the German School on Beach Road and marched off down the peninsula. Americans from a visiting collier, USS Abarenda, followed. German-American relations were based on a common cause; the division of Sāmoa. Members of the German Concordia Club were in the march, followed by assorted papālagi. Near the back was an assortment of mixed culture people, already cursed as ‘afakasi’ or ‘half-caste’. The Sāmoa Weekly Herald said they were ‘all dressed nicely’. Sāmoans came up the rear.

‘We should say that fully 5000 natives were present…,’ the Herald said. ‘During the whole of the celebration the natives behaved on the whole very well.’

Cormoran Korvettenkapitän Hugo Emsmann, 43, insisted he should raise the German flag as he had been longer in Sāmoa than Solf. Kaiser Wilhelm knew him as close friend ‘Emsie’. It meant little to Solf, who would have a lifetime of his own ego issues; the two raised the flag jointly. Emsmann used Wilhelm’s words; ‘Where a German soldier in faithful duty to his fatherland has lost his life and lies buried and where the German Eagle has bitten his fangs into a land this land is German and will remain German… The islands are German and will remain to be German.’ Solf, who read a formal proclamation, said Sāmoa was small, remote and had no commercial future: ‘My congenial duty, therefore, is merely to guard it as what it is – a little paradise – and to do my best to keep the passing serpent out of the Garden of Eden.’ With the flag up everybody walked back to Āpia. The night was marked with a ‘Grand March’ at a hot evening ball, followed by a waltz, polka and quadrille.

Matā’afa Iosefo wrote to the Kaiser thanking him for annexation saying, ‘our desire has been fulfilled.’ Matā’afa accepted that Germany ‘shall be a government into eternity’. He was appointed Le Ali’i Sili - the highest chief of Sāmoa. It was ceremonial, the Kaiser was ‘Tupu Sili’ – supreme ruler.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Field's South Pacific Tides to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.