Luagalau’s killing came one hundred years after German plenipotentiary Wilhelm Solf, along with his servant, arrived in Āpia. His was the prosaic business of putting into effect decisions taken in Europe by white empires dividing up the remnants of places until recently occupied by independent people. By the 20th Century Britain had the biggest empire, leaving unified Germany and a new imperialist, the United States, with scraps like Sāmoa, Tonga, the Solomon Islands and patches of Africa. Solf was part of a compromise that had followed a forgotten war. Peaceful villages scattered along lagoon edges had been pitilessly bombarded by the navies of Britain, Germany and the United States. Motives for killing Sāmoans were many. Through the 19th Century, Sāmoans struggled to retain their culture and their homes.

The western powers had been skillful in one aspect of their hunger, and that was in sending missionaries ahead who were able to successfully indoctrinate local people into responding peacefully to the plunder of their land. The mix of soul-saving men, beachcombers, speculators and the greedy created chaos in the harbour settlement of Āpia, which occasionally spread to the rest of Sāmoa. What became a rivalry over Sāmoa was an attenuated version of what ultimately produced world wars in the 20th century. Sāmoans were not hapless victims; leaders took sides, or resisted them all. Mata’afa Iosefo has the rare distinction of being one of the few commanders of forces to have inflicted defeats on the military sent by London, Berlin and Washington. He was a leader who featured in the western press. Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson referred to him, but Mata’afa’s story mostly slipped from history and the monuments and graves only recall the white men who he inflicted defeat on, as they tried to conquer his homeland. Stevenson, who did nothing for Sāmoa other than profit from it, is better remembered today, even in Sāmoa, than the nation builders.

By 1900, Sāmoa was divided between Germany and the United States (no one wanted Tonga which had a treaty of friendship with Germany). American Sāmoa still remains a lost and little cared for possession of Washington, content with its contribution of foot soldiers and footballers. The contrast with the part that is now Sāmoa was stark. Solf, a crotchety bachelor, became governor of Deutsch-Sāmoa, ruling for Kaiser Wilhelm II who believed any place where German soldiers had shed blood had to be a permanent part of his Deutsches Kaiserreich. New Zealand and British Empire propaganda - coloured strongly by the Great War - has forever tainted Deutsch-Sāmoa and yet it’s 14 year existence was humane, constructive and cultural. Solf, in 10 years, did more for fa’a Sāmoa than 48 years of New Zealand bumbling. It is why this history includes not only the activities of the German settler community (including the clodhopping rise of a Sāmoa Nazi Party) but of Solf and his family following his departure from Sāmoa. He had married while still governor and their first child was born in the governor’s residency at Vailima - making her, if not Sāmoan, then of Sāmoa. That Johanna Solf and daughter Lagi were caught in the resistance struggle against Adolf Hitler, ending up in concentration camps, could seem a tentious connection in a Sāmoan story. For a country considered small and isolated, its connections, within time and geography, are confirmation for Sāmoans that they too matter on a global stage. Apart from anything else, the story of two women from Vailima who fought Nazis and jailed in a women’s concentration camp at Ravensbrück, serves to highlight the now mostly forgotten story of German imperial rule in the Pacific which was not only about Sāmoa.

New Zealand's rule of Sāmoa was miserable, yet its politicians and journalists quickly persuaded themselves that being Anglo-Saxon and British meant that their rule was superior to that of Germans. For a great deal of New Zealand rule, the notion that Sāmoans might be capable of running themselves was regarded as risible. New Zealand at first saw Sāmoa as their prize of war (the only one, other than assorted surrendered German military deritutus) and to criticise was to question the sacrifice of men who died on European battlefields. The propaganda merged seamlessly into unquestioned acceptance that white New Zealanders were better at ruling Polynesian people, as evidenced by their asserted triumph with Maori. Several deceptive narratives so successfully merged that even by 2003, when New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark apologized to Sāmoa, many of her citizens wondered why. Ridiculously, independent Sāmoa still marks Anzac Day - a day for Australian and New Zealand war dead - as if it was about their freedom and not that they had lost it. Only the Covid-19 pandemic finally stopped it.

The worst of New Zealand rule came with a 1918 A/H1N1 influenza epidemic. Certainly part of a global disaster, it produced in Sāmoa a cruel explanation for why the young and small nation of New Zealand was incapable of colonising the South Pacific. It was highlighted by the way American Sāmoa, with sound quarantine, was able to avoid influenza. British Sāmoa suffered a death rate that might well have been the worst in the world. Yet it quickly disappeared from the public mind, first in New Zealand and then, later in Sāmoa itself. Several of the mass graves vanished and few even know of the graves that exist. There is much to still tell of that 1918 disaster, and there has been a lack of accountability for any of it. The role of the New Zealand Army, both in its failure to ensure the virus did not get in and its inability to deal with it, was hidden. What the epidemic also reveals is the way in which history is capable of blotting out events. Clark apologized for the epidemic; a decade on both the epidemic and the apology are forgotten.

The story of the Mau has been told before; including my own version 30 years ago. Within Pacific academic circles, it features in papers and talks, but in a barely accessible way to the ordinary reader. It has only a small place in literature, film or performing arts. As a result, the Mau exists as folklore, at least in Sāmoa. It has not been taken as a meaningful part of the culture; there are monuments to the white dead of various wars in Sāmoa, and a monument to those who fought for the Allies in the world wars. But there is nothing to the Sāmoan who struggle with the Mau for freedom. Indeed, the long serving Human Rights Protection Party government was able to knock down buildings with Mau associations, largely without protest. In New Zealand understanding of the Mau is shallow, a memory held only by those who for various reasons have a connection to it. In the face of little historical understanding, the relationship between New Zealand and Sāmoa is becoming closer, deeper and more personal. Now that both sides are benefiting from the relationship, history is more important than ever.

The period after the Mau was marked by inertia and it is no coincidence that this was the time of the first New Zealand Labour Party Government. In opposition they had called for an end to New Zealand rule, but once in power, a kind of colonial subtext asserted itself. White Labour Party politicians were as good at telling Sāmoans what to do as the conservative ones had been. There was a sense that things could not go on as they had under assorted superannuated warhorses who had administered Sāmoa, but the logical step to self government and independence was not made. The notion of white superiority might have been fading in New Zealand, but the idea of equal status with Polynesians was beyond reach. The stunted growth of the Sāmoan Nazi Party provided some linkage to global events, but it had been Wall Street’s collapse that confirmed to New Zealand that there was no profit in its solitary war prize. It was, however, striking that for most Sāmoans, the Great Depression left village life much as it continued to have been. With the end of New Zealand’s oppression of the Mau, life was good. As a small and unscientific aside, one can see in many of the photos taken at the time, that people were free of the coming curse of obesity. Ailments such as yaws, Hansen's disease and lymphatic filariasis remained chronic and debilitating. Dealing with them was less dependent on New Zealand policy and more on the growing power of medicine.

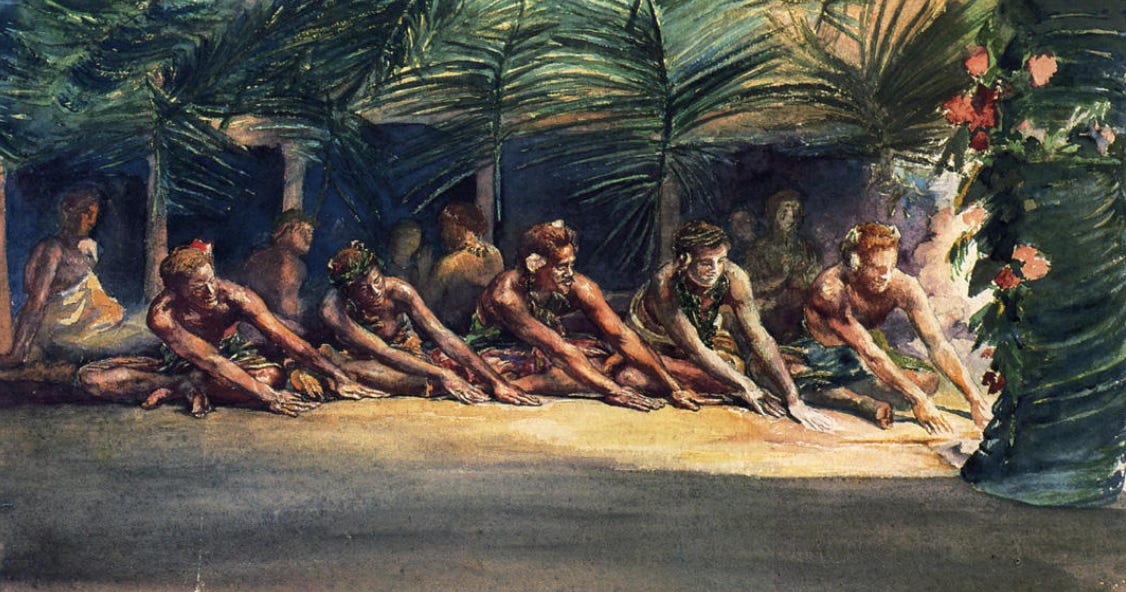

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour, 4,200 kilometres to the north, was to profoundly affect Sāmoa. Imperial Japan had something of a plan to invade Sāmoa, but other than a submarine attack on Pago Pago, no angry shots were fired at British Sāmoa, or from it. The war’s impact on Sāmoa came from the over 14,000 United States Marines who landed at Pago Pago and Āpia to train and prepare. For many naive soldiers, Sāmoa was what paradise was supposed to be like. What happened when the sides met, from sociable dances to assault and rape, did much to define later generations of Sāmoans. American Sāmoa has, since the Vietnam War, provided a disproportionate number of recruits for the US military. It is no accident. Many Sāmoans today have US Marine DNA.

Sāmoa did return to the independence it had always had. With a steady and mostly healthy population, the Independent State of Western Sāmoa (it dropped ‘western’ in 1997) has been stable and confidently governed, despite the occasional political uproar. This book deals with the first decade and a bit of the 21st Century. What comes next is perhaps a great deal more subtle than naval warships bombarding villages, but perhaps it will be more troubling. An enduring obesity epidemic, with non-communicable disease problems, threatens the nation in a more insidious way that influenza did. Isolation used to define Sāmoa and its people; now fibre optic cables have snaked ashore, bringing the same vast knowledge available to anybody, and the same problems. Several books, including the King James Version of the Bible, have had a profound impact on Sāmoa, only time will tell what the Internet and Facebook will do to fa’a Sāmoa. This tsunami of information and gossip, much of it negative, underlines just how significant an understanding of Sāmoa’s history is.

©Michael J Field

My Grandfather died of gunshot wound on Black Saturday.He is buried in Lepea.He still hasn't make it home.