Ships ‘capable of blowing Sāmoans to pieces’

Invincible Strangers 11 - Chapter 3.1

Ships ‘capable of blowing every Sāmoan to pieces’

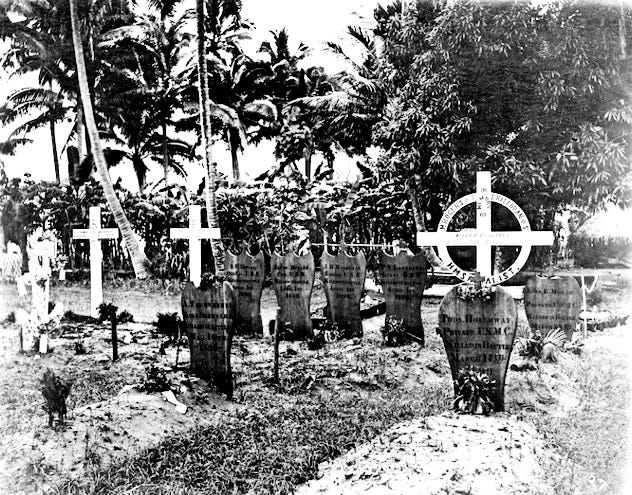

Next day, Easter Sunday, Tupua Tamasese led a party out to the battlefield, returning with seven white corpses.

The British and American dead were buried at Mulinu’ū. At the funeral, described as ‘most impressive’, the US and British flags were intertwined. The dead shared a common sandy grave. The officers’ coffins held only bodies; the heads were missing. Privates had been deprived of their ears. Philippe Charavay, a Marist brother, was sent out to find the heads. He and six locals reached the battlefield late morning. They met a band of 20 Mata’afa warriors who told them they had just buried nine of their own number. Charavey asked about the heads and was told where they were. They found two of the heads, about three kilometres from the battle; Lansdale and Freeman. Mata’afa had given instructions that there should be no head cutting, hence they were not brought to him. Charavey believed it may have been in retaliation for the Malietoa warriors taking a head. Monaghan’s head was found not far from the battlefield.

‘Knowing them well, I easily recognized their features, especially the American officers. They were very little distorted. After washing them in a stream close by, we rolled them up in Samoan mats, placed them in a basket, and set out for Apia…’ The coffins were opened and heads and ears added.

Sāmoan dead were left to their families, uncounted. The American bodies were later exhumed and returned to the US aboard Philadelphia. The coffins were kept on the bridge for the voyage. A monument was erected at Mulinu’ū honouring the Anglo-American dead. There are no monuments to any Sāmoans. Even the voices of those who were there, fighting for Mata’afa, went silent and then were lost in a tragedy 18 years on.

Hufnagel, the plantation manager, was arrested by the British who suspected he knew of the ambush. When it couldn’t be proven, he was released.

Much of the English speaking world heard of the battle first from Francis Ross: ‘while scarcely an enemy could be seen their bullets poured into the British and Americans from three sides.’ He told of beheadings and ear cutting, and said the Anglo-Americans had killed around 30 Mata’afa men. Ross ensured that Monaghan and Lansdale’s last moments were immortalised: ‘‘Monny, you leave me now, I cannot go any further.’

The priest Forestier was contemptuous: ‘It was an act of the greatest folly and madness to send such a handful of men into the enemy's country, and though the bravest of the brave, they could not stand the fire of at least a thousand Samoans who were rendered furious by the fact that they had been bombarded the whole of that morning by one of the British men-of-war, the Royalist.’ Forestier said Mata’afa had given strict orders that his men were not to fight the Anglo-Americans, as he was not at war with them.

‘His warriors have assured us that in many of those inland expeditions of the allied party they could often have killed many, even if they had not annihilated all of them, for the troops often passed close to where the natives lay in ambush,’ Forestier said.

One time they had seen the allies resting, 50 metres away from their stacked up rifles: ‘All this shows how rash it was to expose such valuable lives, and for this the admiral was to blame.‘

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Field's South Pacific Tides to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.