South Pacific naval deployment without captions

Tudor Collins’ magnificent mess of undated images

In the Aotearoa museum trade, Tudor Washington Collins is regarded as a defining photographer of the kauri timber days. Born in 1898 he used a variety of cameras to capture the end of the kauri milling trade.

He had another side though and between the 1940s and the 1960s, he was involved in photographing the life of the Royal New Zealand Navy. When he died in 1970, he had left behind 45,000 images that went into basic storage for 40 years.

Finally in 2013 the entire collection was put into the public domain with the Navy Museum and the Auckland War Memorial Museum holding stewardship.

Many of the navy imagines include remarkable pictures from the South Pacific, a regular sailing ground for the Royal New Zealand Navy. Sadly, they mostly come undated and without captions.

The Navy Museum says there are 10,000 negatives and 3000 prints of naval content alone.

‘The storage of this entirely monochrome collection was not to archival standards, so the material had suffered some damage expected with temperature fluctuations, oxidation, acidic storage boxes and being housed in their original glassine sleeves,’ the Navy Museum says. ‘Along with surface dust and dirt, most negatives showed oxidative silvering, mould and some delamination.’

When he was in RNZN during World War Two, Collins was already an accomplished photographer and casual contributor of news and pictorial images to the New Zealand Herald and the Auckland Weekly News. His picture-taking of the service at this stage was informal, as a petty officer on a patrol launch who was good with a camera.

After the war ship deployment to the Pacific was keenly sought, and Collins travelled with them.

‘Landfall was greeted with generous and heartfelt welcome,’ says the Navy Museum.

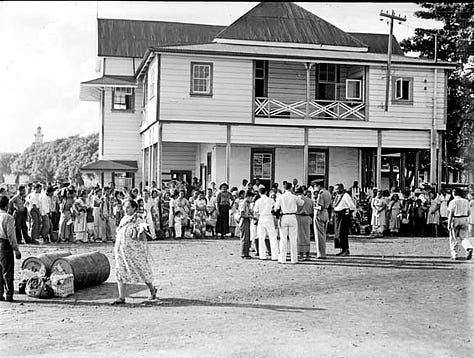

‘The images are exuberant; dancers crowd the foredeck, grinning sailors in baggy shorts are festooned with tropical fruit. In one shot, the naval party saunters along a sandy track, with locals running alongside. There is a pram, dogs, and children, with palms framing the jubilation. There are scenes of mass singing and dancing, speeches, feasting, celebration, and sport.’

One gets the sense of the pictures being important for the way in which Collins focused on apparently ordinary people - both the local people and the ratings. Some of it seems to have greater importance, but the lack of captions is frustrating.

Two make the point, under a general heading ‘Ceremony in Tonga’. Plainly something significant is happening on Nuku’alofa’s Pangai Lahi, the public park next to the old Prime Minister’s Office. Just what is not clear. The photo of the young dancer is striking.

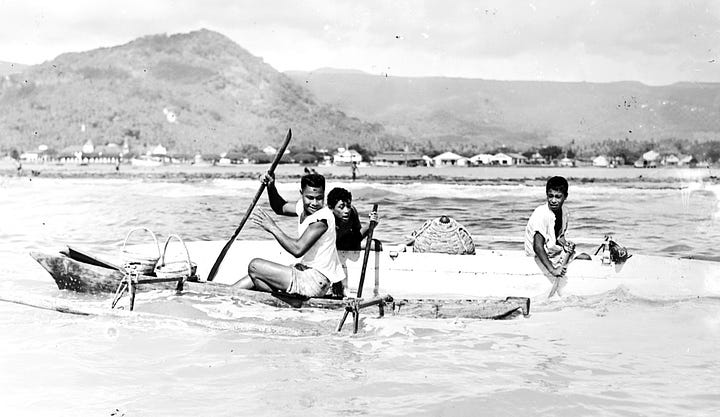

Other photos are beautiful in themselves, even if some further explanation and location would be a help. One labelled ‘Pacific Islanders paddling in canoes’ is a classic action picture; a guess would place it in Apia harbour. A fishing with nets picture could be anywhere in the Pacific; it tends also to underscore how a traditional diet produced fine looking people.

My own favourite image…? Perhaps the one of the rather tall plume feather wearing governor general greeting what looks to be local health staff. He shakes hands with presumably the head nurse, in a rather formal way. No eye contact at all. What makes the image is the woman between them; looking up at this towering fellow with a smile that says she will have a story for a while to tell the family. The way they are all lined up at the beach suggests the place is Tokelau.

©Michael J Field